Mosquito Beach Heyday

Hot Spots

It was with the opening of Joe Chavis’s store after the 1940 hurricane and during a time of harsh racial segregation that “The Factory” (now Mosquito Beach) gained popularity as a social and recreational hub for the area’s black citizens. Prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, most entertainment and recreational venues in Charleston, including public beaches, parks, restaurants, bars, and music halls, prohibited black citizens. Because of this, Mosquito Beach gradually transformed from a small gathering place, into an essential refuge where black citizens could swim, fish, and boat safely, while also freely enjoying fresh seafood, music, drinks, and each other. In the early 1950s, as segregation in both the public and private sectors increased, Joe Chavis’s store was joined by at least three other establishments, all of which were operated by the black farming families who owned the land: the Harborview Club, Machi & Nucca’s pavilion and Jack Walker’s Club.

As the area became more popular for its cuisine, nightlife, access to the water, and proximity to homes, the name “The Factory” gave way to its current moniker, “Mosquito Beach,” aptly named for its year-round infestation of mosquitoes. Early mentions of the name include a 1958 plat for the central lot, and a News & Courier article which described the Harborview Pavilion as “a crowded night spot.”

As one of five black beaches in the Charleston Lowcountry at this time, Mosquito Beach was mostly a destination for local James Island citizens, but also entertained guests from both downtown Charleston and all over the southeast. Although events on Mosquito Beach were not published in Charleston’s major newspapers, many oral histories claim that formal advertisements were not necessary – word of mouth traveled quickly and effectively. Many residents recalled that Mosquito Beach was the place, “to see and be seen,” and it was assumed that most local residents would appear frequently on the strip throughout the summer months. Sol Legare residents remember every business on Mosquito Beach as consistently “jam packed with folks of all ages” every weekend.

Easter Sunday marked the beginning of the social season at Mosquito Beach. This weekend, Labor Day, and the Fourth of July were the busiest times of the year, when patrons “strutted down the strip” to show off their finest wardrobes. Holiday celebrations often included dance contests, boat races and, later, a live broadcast at the pavilion by radio station WPAL, Charleston’s first radio station directed toward African-American listeners. The pavilion, however, was more than just a place to dance, eat, and drink. One resident remembered sitting on the pavilion’s railing for hours to “catch a cool breeze,” listening to music before using the rear deck to “dive off” into the water.

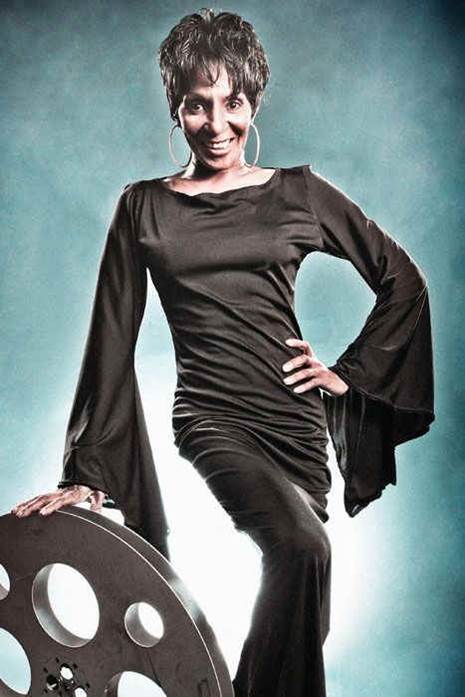

Frankie the Big Bopper, photo from Facebook

Andrew “Apple” Wilder, Jr. (1922-1984) constructed a dance pavilion in 1953 on King Flats Creek directly across from a popular store owned by Joe Chavis. Apple Wilder managed the Harborview Club & Pavilion with his wife Laura, a former oyster factory shucker who served as the Harborview Club’s cook and accountant. To many, Laura was considered the backbone of the business Apple and his wife Laura are pictured here and were also pictured with other Mosquito Beach families on the pavillion in the 1950s. The pavilion was destroyed by Hurricane Gracie in 1959 and never rebuilt. All that remains are the pavilion’s foundation piers, which are present in the marshes of King Flats Creek.

Weekdays were quiet, but starting Friday afternoon, as everyone finished work on nearby farms, the crowds gathered and the party started. Buses brought people in from downtown and other parts of the Charleston Lowcountry on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, as Mosquito Beach became “the dating scene,” “where folks met” throughout the 1950s and 1960s. During the day on the weekends, the gentlemen would “clean up” and play cards while the women cooked. At night, everyone ate, drank, and danced. Meanwhile, activities on the water mostly occurred on Sundays with sponsored boat races with guests “from as far away as Georgetown and Savannah.” A residents remembered Mosquito Beach as the “place to be,” as they “had no place else to have fun on Sundays.”

When Hurricane Gracie swept through in 1959, and destroyed many buildings, including the Harborview Club and Manchi & Nucca’s, the opportunity arose for Apple Wilder to purchase the property immediately west of the Lafayette property from a white real estate mogul. With this purchase, Mosquito Beach became an entirely black-owned strip. The Mosquito Beach of today began to take shape in the post-hurricane building patterns – Mosquito Beach Road lined with two pavilions and four structures: Jack Walker’s Club, Pine Tree Hotel, Uncle Jimmy’s Place and Joe Chavis’s store.

Sol Legare native Susan Chavis wrote in 2015 of the role of Mosquito Beach during the early 1960s:

It was to give African Americans a place to enjoy themselves by ‘strutting’ up and down the area, catching a breeze, listening to a variety of music, shaking a leg, and buying some of the best soul and southern food, and just enjoying each other without the pressures of dividing lines.

“Many residents recalled that Mosquito Beach was the place, ‘to see and be seen’…”

Entertainment

Lady Chablis, a popular drag queen, headquartered in Savannah and celebrated in John Brendt’s book Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, also performed on Mosquito Beach.

Although Mosquito Beach was neither part of the nationally-known Chitlin Circuit nor registered in The Green Book like other larger beach resorts such as Atlantic Beach (near Myrtle Beach), it was a local mecca for homegrown musicians. Edward Wilder (b. 1936) remembered dancing to blues music and doing the shag, traveling from one building to the next on the Mosquito Beach strip. Joe Chavis was known to often play the blues “on a metal washboard with a fork and knife” outside his Seaside Grill while patrons danced on the floor right outside the door.

In addition to jukeboxes there were live broadcasts by radio station WPAL which was owned by Bill Saunders. Disc jockeys and performers made common appearances on Mosquito Beach, including Bob Nichols, the first African-American disc jockey in a full-time capacity in South Carolina. Many credit Nichols who was known for his catchphrase “I can see you out there” – as important to the development of Mosquito Beach, as he “would draw the crowds…every weekend.”

Performers who frequently visited Mosquito Beach on Friday and Saturday evenings, nights when children were typically not present at Mosquito Beach, included John Ford and his live band, and Margo Mayes and her Powder Box Review, known to the Sol Legare residents as “Shake-a-Plenty.” The performance included a 9-foot boa constrictor named Unga and a “semi-strip” act where Unga would “twine” around Mayes. During the summer of 1970, Unga died of suffocation on the way from Columbus, GA to the Charleston Lowcountry, but Mayes told the Evening Post she “already placed an order for a 10-foot boa constrictor” hoping it would arrive before she completed her “engagement at Mosquito Beach.” Lady Chablis, a popular drag queen, headquartered in Savannah and celebrated in John Brendt’s book Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, also performed on Mosquito Beach.

This material was produced with assistance from the African American Civil Rights grant program, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior.

This material was produced with assistance from the African American Civil Rights grant program, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior.